"The most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in our nation's history."

The Snapshot: If you read this week's Slightly Smarter, you got the main finding: ultra-processed food guidance has the strongest evidence, dietary patterns matter more than single nutrients, and the saturated fat reversal is genuinely contested. This is the full analysis—the research, the contested claims broken down, the myths debunked, and how to evaluate nutrition information yourself. [If you want the short weekly version, Slightly Smarter is publishing a 2-minute snapshot of each topic—you can subscribe free and follow along there, too.]

Last week’s Physical Wellness overview is now the evergreen map for Weeks 4–9 (nutrition, strength, sleep, flexibility, neuromotor, cardio). If you want the one-page framework before diving in, start here: Physical Wellness (overview) → https://www.slightlysmarter.com/p/physical-wellness

The Featured Resource

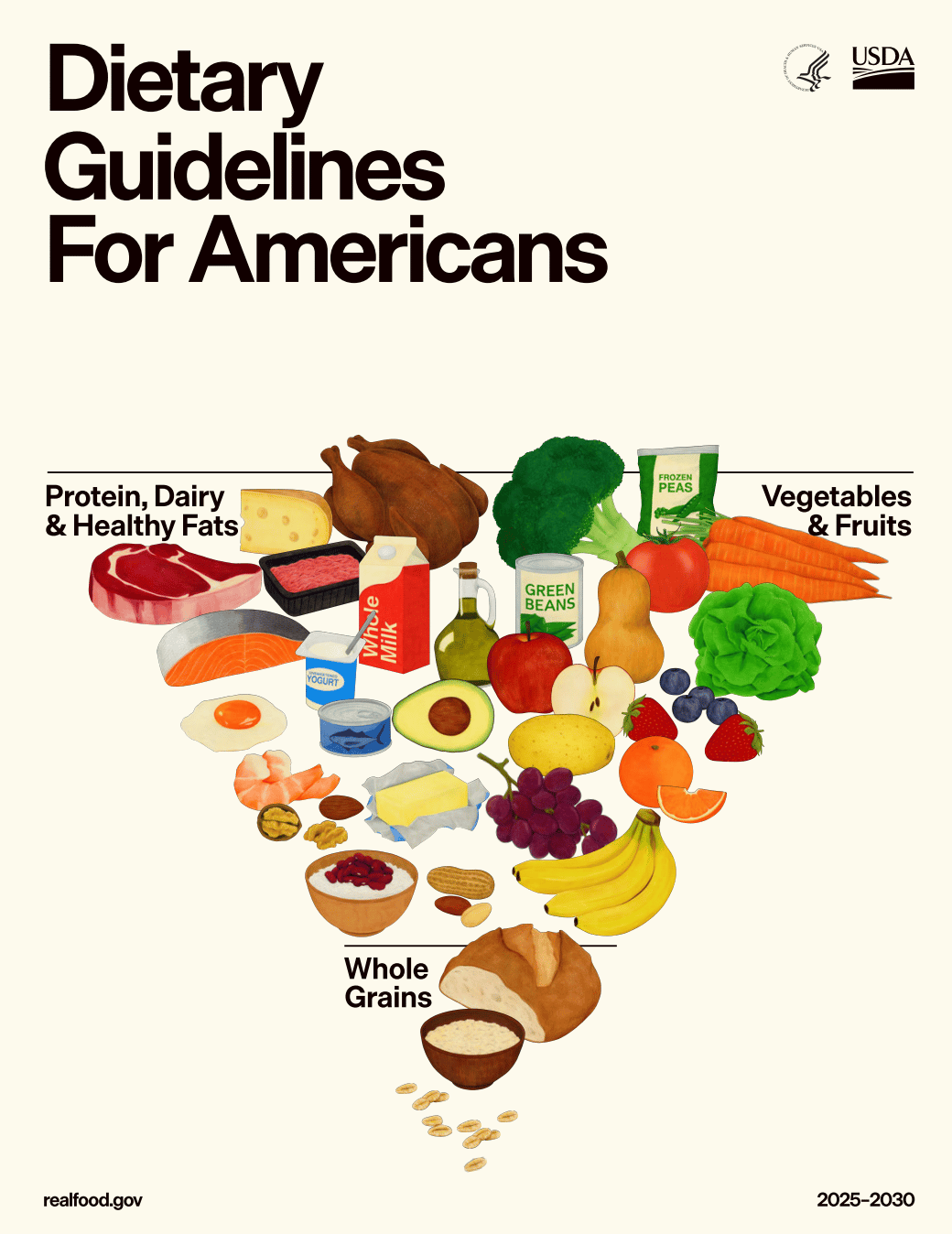

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030

U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Released: January 7, 2026 | Pages: 150+

This isn't a bestseller by a doctor selling supplements. It's the federal nutrition policy document—the one that determines what 30 million kids eat at school lunch, what hospitals serve patients, and what gets taught in nutrition education nationwide.

The Scientific Foundation report is remarkably transparent about what the evidence does and doesn't support. Worth reading the primary source.

The Research: What the Evidence Actually Supports

Ultra-Processed Foods (Tier 1 — Strongest Evidence)

The guidance to avoid ultra-processed foods has the strongest science behind it.

Not "we're getting closer to consensus." Not "these frameworks are converging." No mutual understanding.

The guidance to avoid ultra-processed foods has the strongest science behind it.

Hall et al. (2019) conducted a landmark study at the NIH: 20 adults in a metabolic ward, two weeks on ultra-processed food, two weeks on unprocessed food. Diets matched for calories, protein, fat, carbs, sugar, sodium, and fiber.

Result: On ultra-processed food, people ate 508 more calories per day and gained nearly a pound in two weeks. Same food available. Radically different intake.

This is a randomized controlled trial—the gold standard. It establishes causation, not just correlation.

Lane et al. (2024) synthesized 45 meta-analyses in a BMJ umbrella review covering nearly 10 million participants. Convincing evidence linked ultra-processed food to:

50% higher cardiovascular mortality

12% higher type 2 diabetes risk per serving

48-53% higher odds of anxiety and depression

Verdict: The science strongly supports this guidance.

Dietary Patterns Over Single Nutrients (Tier 1-2)

The guidelines emphasize overall patterns—and the research backs this.

The PREDIMED trial (Estruch et al., 2018) followed 7,447 high-risk adults for a median of 4.8 years. Mediterranean diet plus olive oil or nuts reduced major cardiovascular events by 30% compared to low-fat control.

No single food or supplement has replicated this effect. The pattern matters more than optimizing parts.

Verdict: Strong evidence. Focus on overall dietary patterns, not individual nutrients.

Protein Increase (Tier 2-3)

The new target—1.2-1.6g per kilogram of body weight—is 50% higher than previous guidelines.

A 2022 systematic review found this range supports lean body mass in both younger and older healthy adults, with the strongest evidence for muscle maintenance and sarcopenia prevention. For average adults without specific muscle goals, the benefits are less certain than the ultra-processed food evidence.

Verdict: Reasonable guidance, moderate evidence.

Case Study: How to Evaluate a Contested Claim

The Saturated Fat Reversal

This is what a genuinely contested scientific question looks like. Not misinformation vs. truth—qualified experts, real data, legitimate disagreement. Here's how to evaluate it yourself.

⚠️ CONTESTED TOPIC — The science is genuinely unsettled. Don't let anyone tell you otherwise.

The Traditional Position (AHA, Prior DGAs):

Saturated fat—found abundantly in butter, beef tallow, lard, full-fat milk, cheese, and red meat—raises LDL cholesterol. LDL is causally linked to atherosclerosis—Mendelian randomization studies confirm that people with genetically higher LDL have higher cardiovascular disease rates, regardless of other factors. This mechanism isn't disputed.

Based on this, guidance for decades said: limit saturated fat to <10% of calories, choose skim milk over whole, use vegetable oils instead of butter, reduce red meat. The American Heart Association still holds this position.

What to notice: The mechanism is solid. The question is whether reducing these foods meaningfully affects heart disease outcomes.

The Emerging Challenges:

Several meta-analyses have questioned whether cutting back on saturated fat actually reduces cardiovascular events:

Siri-Tarino et al. (2010): A meta-analysis of 347,747 people found no significant association between saturated fat intake and heart disease.

Astrup et al. (2020): A review in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology concluded: "Most recent meta-analyses found no beneficial effects of reducing SFA intake on CVD and total mortality."

Yamada et al. (2025): A systematic review of 9 RCTs found no significant differences in cardiovascular or all-cause mortality between saturated fat restriction and control groups.

The new DGA cited this body of research when permitting butter, beef tallow, and full-fat dairy.

What to notice: These are meta-analyses and systematic reviews—high on the evidence hierarchy. But hierarchy isn't everything.

The Critiques of the Challenges:

These meta-analyses haven't gone unchallenged:

Industry funding: The Siri-Tarino et al. (2010) study was funded in part by the National Dairy Council. Several Astrup et al. (2020) co-authors had dairy industry ties. The JACC paper was controversial enough that the journal published critical response letters.

The replacement problem: "No effect" findings may reflect what people replaced saturated fat with. Swapping animal fats for refined carbohydrates and sugar appears neutral or harmful. Swapping for olive oil and polyunsaturated fats shows benefit. Many studies didn't control for this.

Willett's critique: Walter Willett (Harvard, 25 years as nutrition chair) and Frank Hu published responses arguing the DGA went further than the evidence supports. They contend the evidence for replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fats reducing CVD remains strong.

What to notice: Funding doesn't automatically invalidate research, but it warrants scrutiny. Methodology matters as much as conclusions. Experts with strong credentials disagree publicly.

Verdict:

Genuinely contested. The mechanism (saturated fat → LDL → atherosclerosis) is solid. Whether cutting specific foods meaningfully reduces heart attacks is disputed. Industry funding clouds research on multiple sides.

The DGA moved one direction; major researchers publicly disagree. Focus on food quality over macronutrient ratios. Avoid absolutist claims either way.

What Wellness Literacy Looks Like Here:

Acknowledge the mechanism is real (saturated fat → LDL → atherosclerosis)

Note the outcome data is mixed

Check funding sources—on all sides

Recognize when qualified experts genuinely disagree

Avoid certainty where the science doesn't support it

Make your own informed choice, knowing the limitations

The Myths: What Persists Despite Evidence

Myth | What the Evidence Actually Shows |

|---|---|

"All carbs are bad" | Carbohydrate source matters. A BMJ meta-analysis of 45 studies found whole grains associated with 17% lower all-cause mortality and 25% lower cardiovascular mortality (Aune et al., 2016). Refined carbs and added sugars are associated with harm—but demonizing an entire macronutrient oversimplifies the science. |

"Fresh produce is always more nutritious than frozen" | Frozen produce is often comparable or more nutritious—flash-frozen at peak ripeness. A two-year study found that after five days of refrigerated storage (typical consumer behavior), frozen produce frequently outperformed "fresh-stored" in vitamin C, vitamin A, and folate content (Li et al., 2017). |

The Red Flags: How to Spot Nutrition BS

These patterns draw from psychological inoculation research on manipulation tactics (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2022)—the same framework behind Foolproof, which we featured in Week 1. Learning to recognize these tactics builds resistance to misinformation across domains.

Eight patterns that signal questionable nutrition claims:

Single study sensationalism — One study, especially preliminary or in mice, presented as definitive

Extreme language — "Miracle," "toxic," "cure," "deadly," "breakthrough" without nuance

Conspiracy framing — "What doctors don't want you to know," "Big Food is hiding this"

Product sales attached — Advice bundled with supplements, tests, or programs

Testimonials over data — Personal stories instead of controlled studies

Missing credentials or conflicts — No relevant expertise, or undisclosed financial interests

Ancient wisdom fallacy — "Our ancestors didn't eat X" (they also died at 35)

All-or-nothing rules — "Never eat X" without acknowledging individual context

The Literacy Lesson: Evaluating Contested Claims

The saturated fat debate isn't a failure of science—it's science working. Contested claims are the norm in nutrition, not the exception.

The skill: When experts disagree publicly, don't pick a side based on who sounds more confident. Instead:

Check the mechanism. Is it plausible? (Saturated fat → LDL → atherosclerosis: yes)

Check the outcomes. Does the mechanism translate to real-world results? (Mixed)

Check the funding. Who paid for the research? (Dairy industry on some; AHA affiliations on others)

Check the consensus. Do major institutions agree? (No—DGA vs. AHA split)

When you find genuine disagreement among qualified experts with real data, that's not a sign you need to research harder. It's a sign the science is unsettled. Act accordingly—with appropriate uncertainty.

The Framework: What Actually Matters

What the DGA 2025-2030 Says:

Change | Old Guidance | New Guidance |

|---|---|---|

Protein | ~0.8g/kg | 1.2-1.6g/kg |

Dairy | Skim or low-fat milk | Full-fat permitted |

Saturated fat sources | Limit butter; avoid tallow | Permitted |

Ultra-processed | Limited mention | Explicitly avoid |

Added sugars | <10% calories | "No amount recommended" |

What the Evidence Tiers Show:

Guidance | Evidence Tier | Verdict |

|---|---|---|

Avoid ultra-processed foods | Tier 1 (RCT + meta-analyses) | Strongly supported |

Dietary patterns over single nutrients | Tier 1-2 (large RCTs) | Strongly supported |

Higher protein | Tier 2-3 (expert consensus) | Reasonably supported |

Saturated fat reversal | Tier 3-4 (contested) | Genuinely debated |

The DGA and the evidence align on the big stuff: whole foods over processed, adequate protein, patterns over parts. Where they diverge (saturated fat), the science is genuinely uncertain.

Verify This

All studies cited are publicly accessible. Search by author name and year, or use the DOIs below.

DGA 2025-2030: dietaryguidelines.gov — full document free

Scientific Foundation: realfood.gov — the evidence review behind the guidelines

Coming Next Week

Week 5: Strength Training

The fitness industry sells complexity—muscle confusion, periodization schemes, exercise "hacks." The science sells simplicity: progressive overload, adequate volume, consistency.

We'll cover what the research actually says about building strength and why most programs overcomplicate it.

Editor's Note

The government changing its mind about butter isn't a scandal. It's science working. Evidence accumulates. Positions update.

The problem is when uncertain guidance gets treated as certain—and when today's guidelines get treated as final rather than our current best understanding.

—Brian

References

Astrup, A., Magkos, F., Bier, D. M., et al. (2020). Saturated fats and health: A reassessment and proposal for food-based recommendations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 76(7), 844-857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.077

Aune, D., Keum, N., Giovannucci, E., et al. (2016). Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality. BMJ, 353, i2716. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2716

Estruch, R., Ros, E., Salas-Salvadó, J., et al. (2018). Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(25), e34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1800389

Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., et al. (2019). Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain. Cell Metabolism, 30(1), 67-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008

Lane, M. M., Gamage, E., Du, S., et al. (2024). Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review. BMJ, 384, e077310. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

Li, L., Pegg, R. B., Eitenmiller, R. R., et al. (2017). Selected nutrient analyses of fresh, fresh-stored, and frozen fruits and vegetables. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 59, 8-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2017.02.002

Nunes, E. A., Colenso-Semple, L., McKellar, S. R., et al. (2022). Systematic review and meta-analysis of protein intake to support muscle mass and function in healthy adults. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 13(2), 795-810. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12922

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2022). How to combat health misinformation: A psychological approach. American Journal of Health Promotion, 36(3), 569-575. https://doi.org/10.1177/08901171211070958

Siri-Tarino, P. W., Sun, Q., Hu, F. B., & Krauss, R. M. (2010). Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(3), 535-546. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.27725

U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2025). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/

Yamada, S., Kamishima, K., Saitoh, M., & Yamazaki, T. (2025). Effects of reducing saturated fatty acid intake on cardiovascular disease. JMA Journal, 8(2), 395-407. https://doi.org/10.31662/jmaj.2024-0185

About the author: Brian S. Dye, Ed.D., is the founder of Applied Wellness, an evidence-based wellness education platform focused on helping people cut through wellness noise and apply credible guidance in real life. Learn more →

This newsletter provides general nutrition education based on published research. It does not constitute medical or dietary advice. Consult a registered dietitian or healthcare provider for personalized guidance.

The Series Ahead

This series will continue to move through Physical Wellness, as we make our way through all of the dimensions of wellness.

Week | Topic | Dimension |

|---|---|---|

1 | Misinformation + Wellness | (The Problem) |

2 | What is Wellness | (The Foundation) |

3 | Physical Wellness | Physical |

4 | Nutrition | Physical |

5 | Strength Training | Physical |

6 | Sleep | Physical |

7 | Flexibility | Physical |

8 | Neuromotor (balance, coordination, agility) | Physical |

9 | Cardio | Physical |

10+ | Remaining Dimensions | All Others |

Each week follows the same structure: what the research says, what's overstated, the myths, and how to verify.